The translation and publication of Cixin Liu’s Three-Body books has been a singular highlight of the science fiction scene in recent years. The Hugo Award-winning opening salvo of said saga took in physics, farming, philosophy and first contact, and that was just for starters. The world was wondrous, the science startling, and although the author’s choice of “a man named ‘humanity'” as that narrative’s central character led to a slight lack of life, The Three-Body Problem promised profundity.

A year later, The Dark Forest delivered. Bolstered by “a complex protagonist, an engrossing, high-stakes story and a truly transcendent setting, The Dark Forest [was] by every measure a better book” than The Three-Body Problem. Not only did it account for its predecessor’s every oversight, it also embiggened the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy brilliantly and explored a series of ideas that astonished even seasoned science fiction readers.

But “no banquet was eternal. Everything had an end. Everything.” And when something you care about does approach that point, all you can do is hope it ends well.

In the first, it’s as expansive a narrative as any I’ve ever read. Most books, at bottom, are brief histories of human beings, but Death’s End is different. It’s a history of the whole of humanity in the whole of the galaxy that begins, albeit briefly, in 1453, continues concurrently with the events of The Three-Body Problem and The Dark Forest, before concluding a matter of millions of years later. All told, the sweep of the story Cixin Liu is determined to depict is absolutely staggering.

For all that, though, Death’s End has a single character at its core rather than the vast casts this series’ readers have had to keep track of in the past. Cheng Xin is a fiercely intelligent if especially sensitive aerospace engineer from the early twenty-first century—the time of the Trisolar Crisis, which period of panic followed the catastrophic first contact chronicled in The Three-Body Problem:

The Trisolar Crisis’ impact on society was far deeper than people had imagined at first. […] In terms of biology, it was equivalent to the moment when the ancestors of mammals climbed from the ocean onto land; in terms of religion, it was akin to when Adam and Eve were banished from Eden; in terms of history and sociology… there are no suitable analogies, even imperfect ones. Compared to the Trisolar Crisis, everything heretofore experienced by human civilisation was nothing. The Crisis shook the very foundation of culture, politics, religion, and economics.

To wit, with a common enemy coming, the people of planet Earth essentially come together and put several survival stratagems into action. The Wallfacers of The Dark Forest were one; the Staircase Project, Cheng Xin’s plan to embed a spy in the Trisolaran ranks—basically by sending a frozen brain into space—is another. It’s desperate, yes, but times like these call for measures like those.

Sadly, the Staircase Project is a failure from the first, or at least seems to be, because the brain—of one of our attractive protagonist’s many admirers, as it happens—is blown off course before it reaches the needed speed. That mishap means the likelihood of the Trisolaran fleet even finding it is low; negligible enough that when Cheng Xin first enters cryogenic suspension, ostensibly to await the next step of the Staircase, it’s really only to make the people that have pinned their hopes on her happy.

In the eyes of historians, the Staircase Project was a typical result of the ill-thought-out impulsiveness that marked the beginning of the Crisis Era, a hastily conducted, poorly planned adventure. In addition to the complete failure to accomplish its objectives, it left nothing of a technological value. […] No one could have predicted that nearly three centuries later, the Staircase Project would bring a ray of hope to an Earth mired in despair.

And Cheng Xin is there to see it. To feel it, even. But so much has changed by the date she’s awakened! Humanity has entered a period known as the Deterrence Era. Following the state of stalemate established by the Wallfacers in The Dark Forest, the Trisolarans have stopped advancing.

Yet there are other threats, because “the universe contains multitudes. You can find any kind of ‘people’ and world. There are idealists like the Zero-Homers, pacifists, philanthropists, and even civilisations dedicated only to art and beauty. But they’re not the mainstream; they cannot change the direction of the universe.” Where, then, is the universe headed? Why, where we all are: towards “the only lighthouse that is always lit. No matter where you sail, ultimately, you must turn toward it. Everything fades […] but Death endures.”

But what if it didn’t? What if the life of the individual, and likewise the life of the universe, could be prolonged to the point that death itself ended? “If so, those who chose hibernation”—people like Cheng Xin—”were taking the first steps on the staircase to life everlasting. For the first time in history, Death itself was no longer fair. The consequences were unimaginable.”

You don’t get to know about those, though. Not because I won’t tell you, but because Death’s End is so stupidly full of electrifying ideas like these that a good many of them are roundly erased mere pages after they’ve been raised. Before you know it the Deterrence Era is over and the Broadcast Era begun, but the Broadcast Era is soon superseded by the Bunker Era, the Bunker Era by the Galaxy Era and the Galaxy Era by the age of the Black Domain.

There’s enough stuff in this one novel to fill trilogies, and a lot of it lands; I got chills during an abstract chat with a four-dimensional entity, and I thrilled when I learned of the escape of a certain spaceship. That said, some of Death’s End‘s overabundance of substance rather drags. Cheng Xin, for instance. She acts as the narrative’s anchor, allowing readers to acclimatise to each new Age just as she has to on every occasion she’s awakened from hibernation. Alas, she also has an anchor’s personality, which is to say, you know… none. She’s pretty and she’s sensitive and, needless to note, she’s a she, yet in every other respect she resembles the bland “man named ‘humanity'” from The Three-Body Problem more closely than The Dark Forest‘s interestingly conflicted curmudgeon of a central character.

Ultimately, it’s the ideas Cixin Liu tends to in Death’s End that are going to grab you, rather than its protagonist. It’s the incredible ambition of this book that you’re going to write home about, as opposed to its fleeting focus on the minor moments. And that’s… disappointing, I dare say. But it’s nowhere near a deal-breaker. I mean, if you want to tell the story of the whole of humanity in the whole of the galaxy, as Cixin Liu attempts to, then the human beings at the heart of such a vast narrative are fated to feel frivolous.

Death’s End bites off more than it can chew, to be sure, and absent the emotional underpinnings of The Dark Forest, it’s more like The Three-Body Problem than the marvellous middle volume of the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy, which somehow managed that balancing act. But I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, here at the end: The Three-Body Problem was awesome. Death’s End is in every sense at least as immense.

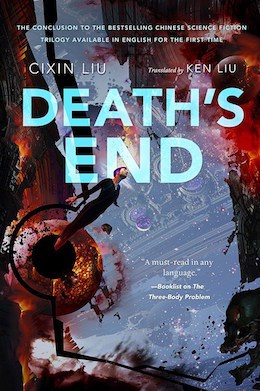

Death’s End is available now from Tor Books, as translated by Ken Liu.

Read excerpts from the novel, beginning with chapter one: “The Death of the Magician“

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He lives with about a bazillion books, his better half and a certain sleekit wee beastie in the central belt of bonnie Scotland.

Nailed it, Niall.

Everyone hurry up and finish it so we can talk about…a lot of things!

Can I read this without reading the first two?

srEDIT, I can’t answer that question(as I’ve not read this new one yet!!)…but why would you not want to read the first two? Absolutely gorgeous, gripping and enthralling books…very much worth the read. When I read TBP for the first time, it was such a joy – I experienced feelings I hadn’t felt reading a new book before in a long time…

I loved “Three Body Problem.” Could not wait for the sequel.

The sheer, unmitigated sexism of the first third (?) of “Dark Forest,” with the ultimate slacker Wallfacer and his Manic Pixie Dream Girl who is literally ordered up and delivered to him, nearly led me to set the whole book aside. I plodded through, not sure if I was more irritated with the author or myself, and was only partly mollified by the last third of the book.

With the end of the trilogy, once again, we have a woman so beautiful and perfect and sweet that men fall over themselves to do things for her; in fact a man literally gives her a piece of the universe when she’s barely spoken to them a few times and not in the years or decades since school. But of course this weird, creepy obsession is reciprocated – how fortunate!

Africa might as well not exist as a continent, along with its portion of the world population, throughout the trilogy. Characters are given little or no “character,” internal life, serving largely as mouthpieces for the needs of the plot. Important Ideas are explained, at great length, not even by characters in the story but the detached, interminable omniscient narrator.

I am reading this book on my Kindle, and at one point looked at the bottom of the screen to see I had only gotten through 30% of the book, which I hoped would be drawing to a conclusion any…. minute…. now…. I feel like I’m in a Smurf cartoon – “Are we there yet, Papa Smurf?” “Not just yet, my little Smurflings!” Over and over and over, I keep hoping… but no. Now there are two plans to see through to the end. Now three stories to unravel (one of the only really engaging parts of the story, perhaps because it isn’t plot, or meditations on Cheng Xin’s goodness and sweetness). Now three more plans to explore over decades and centuries. Only 60% of the book done. Why did I put myself through this? Where is the vitality and excitement of the first book?

The biggest disappointment for me wasn’t the lengthy John-Galt-like pages of pointless narrative, prose, or expository dialog, but rather the author’s constant browbeating of how women can never be great leaders because they are caretakers and not soldiers, and how they long for “real men” with muscles and tall foreheads (seriously). It detracted from the excellent hard sci-fi because it was so persistent and so puerile. It’s a dark novel for sure with many, many, many creative new ideas about space, but jeez dude, put on lid on the MRA stuff.